17个小时!恢复96%肺功能!而且270名病人的肺部功能都正在恢复!

克莱因瓶是一个不可定向的二维紧流形,而球面或轮胎面是可 克莱因瓶 克莱因瓶 定向的二维紧流形。如果观察克莱因瓶,有一点似乎令人困惑--克莱因瓶的瓶颈和瓶身是相交的,换句话说,瓶颈上的某些点和瓶壁上的某些点占据了三维空间中的同一个位置。我们非常接近地球,目前国 AT this unexpected announcement Martin exchanged a swift glance with Corinna. She smiled, drew a five franc piece from her purse and laid it on the table. Martin, wondering, did the same. The Marchand de Bonheur unbuttoned his frock coat and slipped the coins, with a professional air, into his waistcoat pocket. “Mr. Overshaw,” said he, “you must understand, as our charming friend Corinna Hastings and indeed half the Quartier Latin understand, that for such happiness as it may be myIt is one of the many mind-wrecking institutions of which our beloved country is so proud.” “I’m glad to hear you say that,” cried Martin. “I’ve been helping to wreck minds there for the last ten years. I’ve taught French. Not the French language; but examination French. When the son of a greengrocer wants to get a boy-clerkship in the Civil Service can drink all that syrup without being sick I can’t understand,” she remarked. “Omnicomprehension is not vouchsafed even to the very young and innocent, my dear,” said Fortinbras. Martin glanced across the table apprehensively. If ever young woman had been set down that young woman was Corinna Hastings. He feared explosion, annihilation of the down-setter. Nothing of the sort happened. Corinna accepted the rebuff with the meekness of a school-girl and sniffed when Fortinbras was not looking. Again Martin was puzzled, unable to divest himself of his old conception of Corinna. She was Corinna, chartered libertine of the land of Rodolfe, Marcel, Schaunard—he had few impressions of the Quartier Latin later than Henri Murger—and her utterances no matter how illogical were derived from godlike inspiration. He hung on her lips for some inspired and vehement rejoinder to the rebuke of Fortinbras. When none came he realised that in the seedily dressed and now profusely perspiring Marchand de Bonheur she had met an acknowledged master. Who Fortinbras was, whence his origin, what his character and social status, how, save by the precarious methods to which he had alluded, he earned his livelihood, Martin had no idea; but he suddenly conceived an immense respect for Fortinbras. The man hovered over both of them on a higher plane of wisdom. From his kind eyes (to Martin’s simple fancy) beamed uncanny power. He assumed the semblance of an odd sort of god indigenous to this Paris wonderworld. Fortinbras lit another of Martin’s Virginian cigarettes—the little tin box lay open on the table—and leaned back in his chair. “My young friends,” said he, “you have each put before me the circumstances which have made you respectively despair of finding happiness both in the immediate and the distant future. Now as Montaigne says—an author whom I would recommend to you for the edification of your happily remote middle-age, having myself found infinite consolation in his sagacity—as Montaigne says: ‘Men are tormented by the ideas they have concerning things, and not by the things themselves.’ The wise man therefore—the general term, my dear Corinna, includes women—is he who has learned to face things themselves after having dispelled the bogies of his ideas concerning them. It is on this basis that I am about to deliver the judgment for which I have duly received my fee of ten francs.” He moistened his lips with the pink syrup. For the picture you can imagine a grey old lion eating ice-cream. “You, Corinna,” he continued, “belong to the new race of women whose claims on life far exceed their justification. You have as assets youth, a modicum of beauty, a bright intelligence and a stiff little character. But, as you rightly say, you are capable of nothing in the steep range of human effort from painting a picture to washing a baby. Were you not temperamentally puritanical and intellectually obsessed by the modern notion of woman’s right to an independent existence, you would find a means of realising the above-mentioned assets, as your sex has done through the centuries. But in spite of amazonian trifling with romantic-visaged and granite-headed medical students, you cling to the irresponsibilities of a celibate career.” “If he asked me, I’d marry a Turk to-morrow,” said Corinna. “Don’t interrupt,” said Fortinbras. “You disturb the flow of my ideas. I have no doubt that, in your desperate situation, you would promise to marry a Turk; but your essential pusillanimity would make you wriggle out of it at the last moment. You’re like ‘the poor cat in the adage.’?” “What cat?” asked Corinna. “The one in Macbeth, Act i, Scene 3, a play by Shakespeare. ‘Letting “I dare not” wait upon “I would,” like the poor cat i’ the adage.’ You require development, my dear Corinna, out of the cat stage. You have had your head choked with ideas about things in this soul-suffocating Paris, and the ideas are tormenting you; but you’ve never been at grips with things themselves. As for our excellent Martin, he has not even arrived at the stage of the desirous cat.” The smile that lit up his coarse, lined features, and the musical suavity of his voice divested the words of offence. Martin, with a laugh, assented to the proposition. “He, too, needs development,” Fortinbras went on. “Or rather, not so much development as a collection of soul-material from which development may proceed. Your one accomplishment, I understand, is riding a bicycle. Let us take that as the germ from which the tree of happiness may spring. Do you bicycle, Corinna?” “I can, of course. But I hate it.” “You don’t,” replied Fortinbras quickly. “You hate your own idea of it. You’ll begin your course of happiness by sweeping away all your ideas concerning bicycling and coming to bicycling itself.” “I never heard anything so idiotic,” declared Corinna. “Doubtless,” smiled Fortinbras. “You haven’t heard everything. Go on your knees and thank God for it. I repeat—or amplify my prescription. Go forth both of you on bicycles into the wide world. They will not be Wheels of Chance, but Wheels of Destiny. Go through the broad land of France filling your souls with sunshine and freedom and your throats with salutary and thirst-provoking dust. Have no care for the morrow and look at the future through the golden haze of eventide.” “There’s nothing I should like better,” said Martin, with a glance at Corinna, “but I can’t afford it. I must get back to London to look out for an engagement.” Fortinbras mopped his brow with an over-fatigued pocket-handkerchief. “What did you pay me five francs for? For the pleasure of hearing me talk, or for the value of my counsel?” “I must look at things practically,” said Martin. “But, good God!” cried Fortinbras, with soft uplifted hands, “what is there more practical, more commonplace, less romantic in the world than riding a bicycle? You want to emerge from your Slough of Despond, don’t you?” “Of course,” said Martin. “Then I say—get on a bicycle and ride out of it. Practical to the point of pathos.” Martin objected: “No one will pay me for careering through France on a bicycle. I’ve got to live, and for the matter of fact, so has Corinna.” “But, my dear young friend, she has twenty pounds. You, on your own showing have forty. Sixty pounds between you. A fortune! You both are tormented by the idea of what will happen when the Pactolus runs dry. Banish that pestilential miasma from your minds. Go on the adventure.” In poetic terms he set forth the delights of that admirable vagabondage. His eloquence sent a thrill through Martin’s veins, causing his blood to tingle. Before him new horizons broadened. He felt the necessity of the immediate securing of an engagement grow less insistent. If he got home with twenty pounds in his pocket, even fifteen, at a pinch ten, he could manage to subsist until he found work. And perhaps this blandly authoritative, though seedy angel really saw into the future. The temptation fascinated him. He glanced again at Corinna, who sat demure and silent, her chin propped on her fists, and his heart sank. The proposition was absurd. How could he ride abroad, for an indefinite number of days and nights with a young unmarried woman? Of himself he had no fear. Undesirous cat though he was, sent forth on the journey into the world to learn desire, he could not but remain a gentleman. In his charge she would enjoy a sister’s sanctity. But she would never consent. She could not. No matter how profound her belief in his chivalry, her maiden modesty would revolt. Her reputation would be gone. One whisper in Wendlebury of such gipsying and scandal with bared scissor-points would arrest her on the station platform. And while these thoughts agitated his mind, and Corinna kept her eyes always demure and somewhat ironical on Fortinbras, the latter continued to talk. “I’m not advising you,” said he, “to pedal away like little Pilgrims into the Unknown. I propose for you an objective. In the little town of Brant?me in the Dordogne, made illustrious by one of the quaintest of French writers——” “The Abbé Brant?me of ‘La Vie des Dames Galantes’?” asked Corinna. Martin gasped. “You don’t know that book?” “By heart,” she replied mischievously, in order to shock Martin. As a matter of fact she had but turned over the pages of the immortal work and laid it down, disconcerted both by the archaic French and the full flavour of such an anecdote or two as she could understand. “In the little town of Brant?me,” Fortinbras continued after a pause, “you will find an hotel called the H?tel des Grottes, kept by an excellent and massive man by the name of Bigourdin, a poet and a philosopher and a mighty maker of paté de foie gras. A line from me would put you on his lowest tariff, for he has a descending scale of charges, one for motorists, another for commercial travellers and a third for human beings.” “It would be utterly delightful,” Martin interrupted, “if it were possible.” “Why shouldn’t it be possible?” asked Corinna with a calm glance. “You and I—alone—the proprieties——” he stammered. Again Corinna burst out laughing. “Is that what’s worrying you? My poor Martin, you’re too comic. What are you afraid of? I promise you I’ll respect maiden modesty. My word of honour.” “It is entirely on your account. But if you don’t mind—” said Martin politely. “I assure you I don’t mind in the least,” replied Corinna with equal politeness. “But supposing,” she turned to Fortinbras, “we do go on this journey, what should we do when we got to the great Monsieur Bigourdin?” “You would sun yourselves in his wisdom,” replied Fortinbras, “and convey my love to my little daughter Félise.” If Fortinbras had alluded to his possession of a steam-yacht Corinna could not have been more astonished. To her he was merely the Marchand de Bonheur, eccentric Bohemian, half charlatan, half good-fellow, without private life or kindred. She sat bolt upright. “You have a daughter?” “Why not? Am I not a man? Haven’t I lived my life? Haven’t I had my share of its joys and sorrows? Why should it surprise you that I have a daughter?” Corinna reddened. “You haven’t told me about her before.” “When do I have the occasion, in this world of students, to speak of things precious to me? I tell you now. I am sending you to her—she is twenty—and to my excellent brother-in-law Bigourdin, because I think you are good children, and I should like to give you a bit of my heart for my ten francs.” “Fortinbras,” said Corinna, with a quick outstretch of her arm, “I’m a beast. Tell me, what is she like?” “To me,” smiled Fortinbras, “she is like one of the wild flowers from which Alpine honey is made. To other people she is doubtless a well-mannered commonplace young person. You will see her and judge for yourselves.” “How far is it from Paris to Brant?me?” asked Martin. “Roughly about five hundred kilometres—under three hundred miles. Take your time. You have sixty pounds’ worth of sunny hours before you—and there is much to be learned in three hundred miles of France. In a few weeks’ time I will join you at Brant?me—journeying by train as befits my soberer age—I go there a certain number of times a year to see Félise. Then, if you will continue to favour me with your patronage, we shall have another consultation.” There was a brief silence. Fortinbras looked from one young face to the other. Then he brought his hands down with a soft thump on the table. “You hesitate?” he cried indignantly. “You’re afraid to take your poor, little lives in your hands even for a few weeks?” He pushed back his chair and rose and swept a banning gesture, “I have nothing more to do with you. For profitless advice my conscience allows me to charge nothing.” He tore open his frock coat and his fingers diving into his waistcoat pocket brought forth and threw down the two five-franc pieces. “Go your ways,” said he. At this dramatic moment both the young people sprang protesting to their feet. “What are you talking about? We’re going to Brant?me,” cried Corinna, gripping the lapels of his coat. “Of course we are,” exclaimed Martin, scared at the prospect of losing the inspired counsellor. “Then why aren’t you more enthusiastic?” asked Fortinbras. “But we are enthusiastic,” Corinna declared. “We’ll start to-morrow,” said Martin. “At six o’clock in the morning,” said Corinna. “At five, if you like,” said Martin. Fortinbras embraced them both in a capacious smile, as he deliberately repocketed the coins. “That is well, my children. But don’t do too many unaccustomed things at once. In the Dordogne you can rise at five—with enjoyment and impunity. In Paris, your meeting at that hour would be fraught with mutual antipathy, and you would not find a shop open where you could hire or buy your bicycles.” “I’ve got one,” said Corinna. “So have I,” said Martin; “but it’s in London.” Fortinbras extracted from his person a dim, chainless watch. “It is now a quarter past one. Time for honest folk to be abed. Meet me here at eleven o’clock to-morrow, booted and spurred, with but a scrip at the back of your bicycles, and I will hand you letters to Félise and the poetic and philosophic Bigourdin, and now,” said he, “with your permission, I will ring for Auguste.” Auguste appeared and Martin, waving aside the protests of Corinna, paid the modest bill. In the airless street Fortinbras bade them an impressive good night and disappeared in the byways of the sultry city. Martin accompanied Corinna to the gaunt neighbouring building wherein her eyrie was situate. Both were tongue-tied, shy, embarrassed by the prospect of the intimate adventure to which they had pledged themselves. When the great door, swung open by the hidden concierge, at Corinna’s ring, invited her entrance, they shook hands perfunctorily.际天文学界普遍认为此距离在100光年以内,它就能够对地球的生物圈产生明显的影响,这样的超新星被称为近地超新星。有研究认为,在地球历史上的奥陶纪大灭绝,就是一颗近地超新星引起的,这次灭绝导致当时地球近60%的海洋生物消失。[78]

克莱因瓶是一个不可定向的二维紧流形,而球面或轮胎面是可 克莱因瓶 克莱因瓶 定向的二维紧流形。如果观察克莱因瓶,有一点似乎令人困惑--克莱因瓶的瓶颈和瓶身是相交的,换句话说,瓶颈上的某些点和瓶壁上的某些点占据了三维空间 vast monument of sideboard to commonplace of chair, from glittering palisade of fender to long lying bastion of couch, creeps by defences of walls noting each comfortable issue, prowls through lanes and squares innumerable formed by intricacies of furniture; and having once gone through the grave business, worries its head no more about topography and points of interests, but settles down to serene enjoyment of such features of the place as have appealed to its ?sthetic or grosser instincts. In this respect the average human is nearer a cat than he cares to realise. The first hour on board a strange ship is generally devoted to an exhaustive exploration never repeated during the rest of the voyage, and doubtless a prisoner’s first act on being locked into his cell is to creep round the confined space and familiarise himself with his depressing installation. Obeying this instinct common to cats and men, Martin and Corinna, as soon as they had finished breakfast the next morning, wandered forth and explored Brant?me. They visited the grey remains of the old abbey begun by Charlemagne. But Villon writing in the 15th Century and asking “Mais où est le preux Charlemaigne?” might have asked with equal sense of the transitory nature of human things: “Where is the Abbey which the knightly Charlemagne did piously build in Brant?me?” For the Normans came and destroyed it and one eleventh-century tower protecting a Romanesque Gothic church alone tells where the abbey stood. Strolling down to the river level along the dusty, shady road, they came to the terraced hill-side, past which the river once infinitely furious must have torn its way. In the sheer rock were doors of human dwellings, numbered sedately like the houses of a smug row. Above them, at the height of a cottage roof, stretched a grassy plain, from which, corresponding with each homestead, emerged the short stump of a chimney emitting thin smoke from the hearth beneath. Before one of the open doors they halted. Children were playing in the one room which made up the entire habitation. They had the impression of a vague bed in the gloom, a table, a chair or two, cooking utensils by the rude chimney-piece, bunks fitted into the living rock at the sides. The children might have been Peter Pan and Wendy and Michael and John and the rest of the delectable company, and the chimney-stump above them might have been replaced by Michael’s silk hat, and on the green sward around it pirates and Red Indians might have fought undetected by the happy denizens below. Thus announced Corinna with lighter fancy. But Martin, serious exponent of truth, explained that the monks, in the desolate times when their Abbey was rebuilding had hewn out these abodes for cells and had dwelt in them many many years; and to prove it, having conferred, before her descent to breakfast, with the excellent Monsieur Bigourdin, he led her to a neighbouring cave, called in the district, Les Grottes—Hence the name of Bigourdin’s hotel—which the good monks, their pious aspiration far exceeding their powers of artistic execution, had adorned with grotesque and primitive carvings in bas-relief, representing the Last Judgment and the Crucifixion. They paused to admire the Renaissance Fontaine Médicis, set in startling contrast against the rugged background of rock, with its graceful balustrade and its medallion enclosing the bust of the worthy Pierre de Bourdeille, Abbé de Brant?me, the immortal chronicler of horrific scandals; and they crossed the Pont des Barris, and wandered by the quays where men angled patiently for deriding fish, and women below at the water’s edge beat their laundry with lusty arms; and so past the row of dwellings old and new huddled together, a decaying thirteenth-century house with its heavy corbellings and a bit of rounded turret lost in the masonry jostling a perky modern café decked with iron balconies painted green, until they came to the end of the bridge that commands the main entrance to the tiny water-girt town. They plunged into it with childlike curiosity. In the Rue de Périgueux they stood entranced before the shop fronts of that wondrous thoroughfare alive with the traffic of an occasional ox-cart, a rusty one-horse omnibus labelled “Service de Ville” and some prehistoric automobile wheezing by, a clattering impertinence. For there were shops in Brant?me of fair pretension—is it not the chef lieu du Canton?—and you could buy articles de Paris at most three years old. And there was a Pharmacie Internationale, so called because there you could obtain Pear’s soap and Eno’s Fruit salt; and a draper’s where were exposed for sale frilleries which struck Martin as marvellous, but at which Corinna curved a supercilious lip; and a shop ambitiously blazoned behind whose plate-glass windows could be seen a porcelain bath-tub and other adjuncts of the luxurious bathroom, on one of which, sole occupant of the establishment, a little pig-tailed girl was seated eating from a porringer on her knees; and there were all kinds of other shops including one which sold cabbages and salsifies and charcoal and petrol and picture postcards and rusty iron and vintage eggs and guano and all manner of fantastic dirt. And there was the Librairie de la Dordogne which smiled at you when you asked for devotional pictures or tin-tacks, but gasped when you demanded books. Martin and Corinna, however, demanded them with British insensibility and marched away with an armful of cheap reprints of French classics disinterred from a tomb beneath the counter. But before they went, Martin asked: “But have you nothing new? Nothing from Paris that has just appeared?” “Voici, monsieur,” replied the elderly proprietress of the Library of the Dordogne, plucking a volume from a speckled shelf at the back of the shop. “On trouve ?a très joli.” And she handed him Le Ma?tre de Forges, by Georges Ohnet. “But this, madam,” said Martin, examining the venerable unsold copy, “was published in 1882.” “I regret, monsieur,” said the lady, “we have nothing more recent.” “I’ll buy it if it breaks me—as a curiosity,” cried Corinna, and she counted out two francs, seventy-five centimes. “Ninety-five,” said the bookseller—she was speckled and dusty and colourless like the back of her library——” “But in Paris——” “In Paris it is different, mademoiselle. We are here en province.” Corinna added the extra twopence and went out with Martin, grasping her prize. “This is the deliciousest place in the world,” she laughed. “Eighteen eighty-two! Why, that’s years before I was born!” “But what on earth are we going to do for books here?” Martin asked anxiously. “There is always the railway station,” said Corinna. “And if you kiss the old lady at the bookstall nicely, she will get you anything you want.” “The ways of provincial France,” said Martin, “take a good deal of finding out!” Thus began their first day in Brant?me. It ended peacefully. Another day passed and yet another and many more, and they lived in lotus land. Soon after their arrival came their luggage from Paris, and they were enabled to change the aspect of the road-worn vagabond for that of neat suburban English folk and as such gained the approbation of the small community. They had little else to do but continue to repeat their exploration. In their unadventurous wanderings Félise sometimes accompanied them and shyly spoke her halting English. To Corinna alone she could chatter with quaint ungrammatical fluency; but in Martin’s presence she blushed confusedly at every broken sentence. All her young life she had lived in her mother’s land and spoken her mother’s tongue. She had a vague notion that legally she was English, and she took mighty pride in it, but by training and mental habit she was the little French bourgeoise, through and through. With Martin alone, however, she abandoned all attempts at English, and gradually her shyness disappeared. She gave the first signs of confidence by speaking of her mother in Paris as of a dream woman of wonderful excellencies. “You see her often, mademoiselle?” Martin asked politely. “Alas! no, Monsieur Martin.” She shook her head sadly and gazed into the distance. They were idling on one of the bridges while Corinna a few feet away made a rapid sketch. “But your father?” “Ah, yes. He comes four times a year. It is not that I do not love him. J’adore papa. Every one does. You cannot help it. But it is not the same thing. A mother——” “I know, mademoiselle,” said Martin. “My mother died a few months ago.” She looked at him with quick tenderness. “That must have caused you much pain.” “Yes, mademoiselle,” said Martin simply, and he smiled for the first time into her eyes, realising quite suddenly that beneath them lay deep wells of sympathy and understanding. “Perhaps one of these days you will let me talk to you about her,” he added. She flushed. “Why, yes. Talking relieves the heart.” She used the French word “soulager”—that word of deep-mouthed comfort. “It does. And your mother, Mademoiselle Félise?” “She cannot walk,” she sighed. “All these years she has lain on her bed—ever since I left her when I was quite little. So you see, she cannot come to see me.” “But you might go to Paris.” “We do not travel much in Brant?me,” replied Félise. “Then you have not seen her——” “No. But I remember her. She was so beautiful and so tender—she had chestnut hair. My father says she has not changed at all. And she writes to me every week, Monsieur Martin. And there she lies day after day, always suffering, but always sweet and patient and never complaining. She is an angel.” After a little pause, she raised her face to him—“But here am I talking of my mother, when you asked me to let you talk of yours.” So Martin then and on many occasions afterwards spoke to her of one that was dead more intimately than he could speak to Corinna, who seemed impatient of the expression of simple emotions. Corinna he would never have allowed to see tears come into his eyes; but with Félise it did not matter. Her own eyes filled too in sympathy. And this was the beginning of a quiet understanding between them. Perhaps it might have been the beginning of something deeper on Martin’s side had not Bigourdin taken an early opportunity of expounding certain matrimonial schemes of his own with regard to Félise. It had all been arranged, said he, many years ago. His good neighbour, Monsieur Viriot, marchand de vins en gros—oh, a man everything there was of the most solid, had an only son; and he, Bigourdin, had an only niece for whom he had set apart a substantial dowry. A hundred thousand francs. There were not many girls in Brant?me who could hide as much as that in their bridal veils. It was the most natural thing in the world that Lucien should marry Félise—nay, more, an ordinance of the bon Dieu. Lucien had been absent some time doing his military service. That would soon be over. He would enter his father’s business. The formal demand in marriage would be made and they would celebrate the fian?ailles before the end of the year. “Does Mademoiselle Félise care for Lucien?” asked Martin. Bigourdin shrugged his mountainous shoulders. “He does not displease her. What more do we want? She is a good little girl, and knows that she can entrust her happiness to my hands. And Lucien is a capital fellow. They will be very happy.” Thus he warned a sensitive Martin off philandering paths, and, with his French adroitness, separated youth and maiden as much as possible. And this was not difficult. You see Félise acted as manageress in the H?tel des Grottes, and her activities were innumerable. There was the kitchen to be ruled, an eye to be kept on the handle of the basket—if it danced too much, according to the French phrase, the cook was exceeding her commission of a sou in the franc; there were the bedrooms and clean dry linen to be seen to, and the doings of Polydore, the unclean, and of Baptiste, the haphazard, to be watched; there were daily bills to be made out, accounts to be balanced, impatient bagmen to be cajoled or rebuked; orders for paté de foie gras and truffles to be despatched—the H?tel des Grottes had a famous manufactory of these delights and during autumn and winter supported a hive of workers and the shelves in the cool store-house were filled with appetising jars; and then the laundry and the mending and the polishing of the famous bathroom—ma foi, there was enough to keep one small manageress busy. Like a bon h?telier, Bigourdin himself supervised all these important matters, ordering and controlling, as an administrator, but Félise was the executive. And like an obedient and happy little executive Félise did not notice a subtle increase in her duties. Nor did Martin, honest soul, in whose eyes a betrothed maiden was as sacred as a married woman, remark any change in facilities of intercourse. For him she flashed, a gracious figure, across the half real tapestry of his present life. A kindly word, a smiling glance, on passing, sufficed for the maintenance of his pleasant understanding with Félise. For fe中的同一个位置。我们可以把克莱因瓶放在四维空间中理解:克莱因瓶是一个在四维空间中才可能真正表现出来的曲面。如果我们一定要把它表现在我们生活的 对他国的影响 在教会严密控制下的中世纪,也发生过轰轰烈烈的宗教革命。因为天主教的很多教义不符合圣经的教诲,而加入了太多教皇的个人意志以及各类神学家的自身成果,所以很多信徒开始质疑天主教的教义和组织,发起回归圣经的行动来。捷克的爱国主义者、布拉格大学校长扬·胡斯(1369~1415年)在君士坦丁堡的宗教会议上公开谴责德意志封建主与天主教会对捷克的压迫和剥削。他虽然被反动教会处以火刑,但他的革命活动在社会上引起了强烈的反应。捷克农民在胡斯党人的旗帜下举行起义,这次运动也波及波兰。1517年,在德国,马丁·路德(1483~1546年)反对教会贩卖赎罪符,与罗马教皇公开决裂。1521年,路德又在沃尔姆国会上揭露罗马教廷的罪恶,并提出建立基督教新教的主张。新教的教义得到许多国家的支持,波兰也深受影响

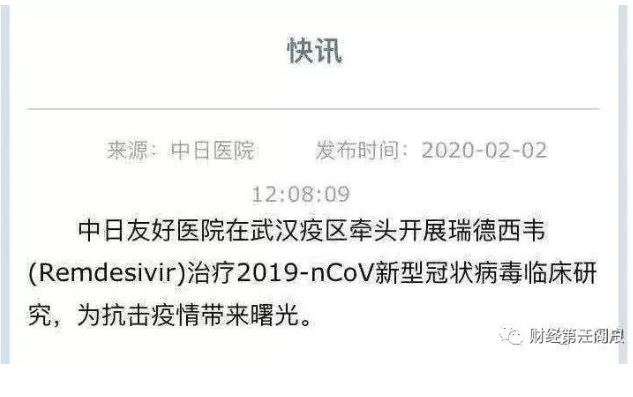

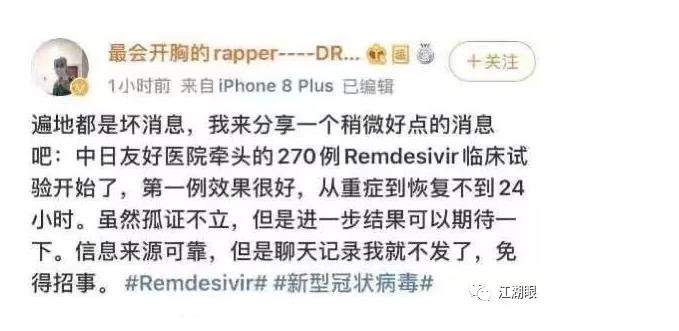

著名的北京中日友好医院曹彬医生团队在疫情发生后赶赴武汉,通过一系列研究在2月3日凌晨起对瑞德西韦(Remdesivir)进行了临床试验证明,结果显示效果良好!——用药以后17个小时,就恢复了96%的肺功能!到2月4日,所有参加临床试验的270名病人的肺部功能都正在恢复!通过此次试验,而且是200多名患者的临床试验,已经进一步验证该药物的安全性和有效性了!天佑中华!就在临床试验效果不错的消息传来,高层就立即做出相应,可谓夜以继日在奋战!就在今天下午,科技部已经宣布,一批瑞德西韦药物于今天下午抵达国内。经过反复试验对比:发现阿比朵尔、达芦那韦两种药被证明可以有效抑制新型冠状病毒。

专家组称:根据初步测试,在体外细胞实验中显示:(1)阿比朵尔在10~30微摩尔浓度下,与药物未处理的对照组比较,能有效抑制冠状病毒达到60倍,并且显著抑制病毒对细胞的病变效应。(2)达芦那韦在300微摩尔浓度下,能显著抑制病毒复制,与未用药物处理组比较,抑制效率达280倍。又一个有效的治疗方案!需要提醒大家的是,这两种药物都是处方药,患者一定要在医生的指导下服用。

2月2日14:00,泰国副总理阿努廷公布了泰国在当前治疗新型冠状病毒肺炎的进展——使用艾滋病压制治疗药物及抗流感病毒两大组合疗法,重新制定出新式医疗方案。治疗结果显示,在该医院接受该疗法的新冠肺炎病例,在12小时后病情好转,48小时检测结果为阴性。

来自武汉的患者已经70多岁,到Rajavithi医院的时候,肺部炎症情况已经十分严重,肺部充血,需要借用设备辅助呼吸,并且患者本身有高血压及心脏病等随身疾病史,综合来看,该患者感染情况属于较为严重一列。泰国医疗专家组,通过综合考虑及临床实验等,通过HIV抗逆转录病毒药物与抗流感药物联合给药的方案:每天早-晚服用HIV抗逆转录病毒药物,同时每天早-晚服用抗流感病毒奥司他韦Oseltamivir,病人竟然全面退烧!12小时好转!48小时就由阳转阴!卫生部官方团队和泰国朱拉隆功医院在内的权威机构帮助反复验证了该结果—48小时,阴性!并将第一手资料和方案分享给中国!不止如此,还有大招,有了药物还有专家一起来助阵!真可谓得道多助,天佑中国!抗战胜利的号角已经吹响,胜利就在眼前。请一起为祖国加油,为武汉加油吧!

无论您有多忙,请花1秒钟时间把它放到你的圈子里!可能您的朋友也需要!谢谢!

辽公网安备:

辽公网安备: